The past reaches us through the medium of stories. The telling of these stories uses different cultural means or tools: words, pictures, sounds. Thus our understanding of past times is created by means of these different types of information, which intertwine and become whole within our consciousness.

The way in which different novels, films, history books, old photos, and other such things enter into dialogue with one another in human consciousness is an interesting, but highly complex process. Like the way in which the majority of us are unable to keep track of the constant trains of thought circulating in our heads, we also do not notice the infinite connections that our brain is constantly making in its interactions with the world. However, even attempts to draw attention to this process may give us an idea of how we make the past understandable to ourselves. This is precisely what we are attempting in the current tutorial.

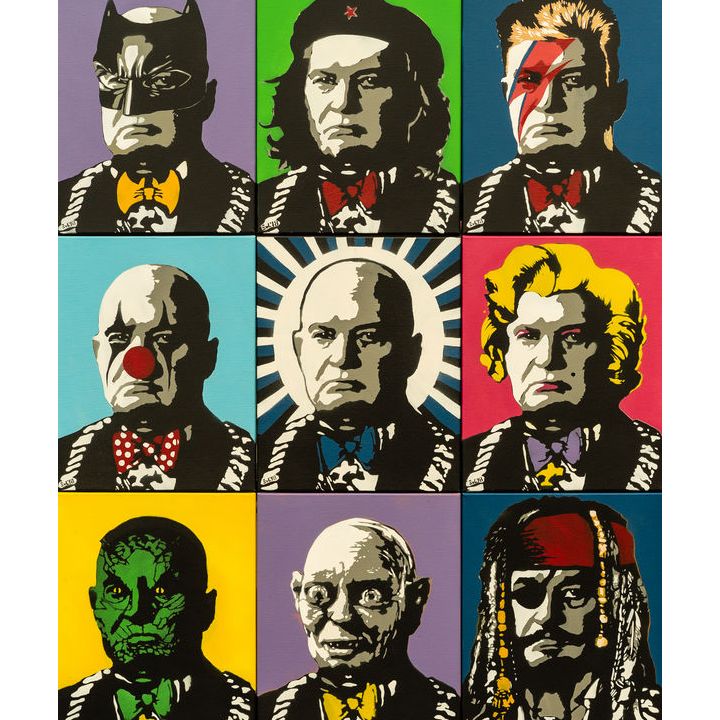

History exists in a dialogue with different cultural texts. Edward von Lõngus "Different faces of the President Päts".

Imagine, for instance, that somebody is telling a story about deportation. The hearer of this story is not only receiving the spoken words and their meanings. Instead, the listener’s consciousness begins to supplement the received information with pictures/images, as well as, in certain cases, sounds, thereby making the received story familiar, like other experiences derived from the real world. On the one hand, this makes it easier for a fellow human being to relate to the storyteller, and on the other hand, it helps them appropriate the information more efficiently. For example, if the setting of the story was a train station, the image of some train station may flash up in the viewer’s mind, a familiar one they have either visited or seen in a photograph.

The materials used in creating this visual picture are predominantly acquired by our consciousness through earlier cultural experiences. Maybe the listener has seen some kind of feature film or documentary about deportation; or perhaps they have retained some illustrations from a history textbook, or history museum exhibition dedicated to the topic. This knowledge begins to supplement the information heard in the story in a parallel manner. And it is not necessary that our consciousness is inspired by only what you would call historically “correct” sources. For example, if a grandmother tells this story to a small child who has no previous contact with the era, the child may find parallels in a fairy tale book, which in this case operates as the visual language used in creating a memory. In this scenario, the story that was told to the child may create a picture of the past where grandmother appears as the child Red Riding Hood, and those deporting her as evil wolves.

Drawing attention to what occurs in our consciousness when we hear a story about the past makes it clear that a person’s historical memory is not only a storehouse of information, but also a creative mechanism constantly combining different interpretations of the past, translating them into different cultural languages, and creating new stories. Consequently, remembering is a creative activity — both at the level of the individual, as well as the level of culture.